The Arrival of Easter

Below, Robert Quinney discusses our latest playlist, which you can listen to here.

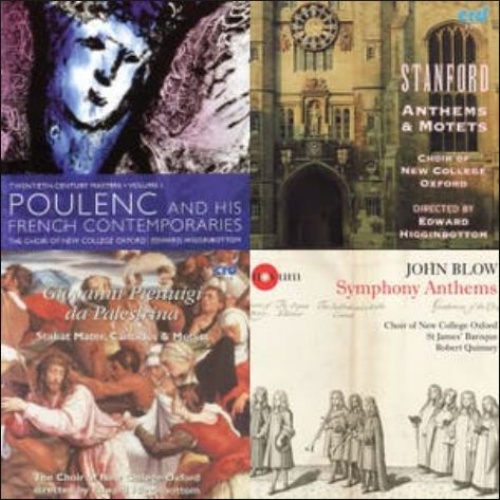

A very Happy Easter to all our listeners! Like all church musicians I’ve been well away from the choir stalls and organ loft for weeks now, and missing all of that very much. But here at New College we’ve been taking the opportunity unexpectedly presented by lockdown to look back at our discography, and sort it into playlists for Spotify. We hope this will give our friends around the world a chance to hear familiar and unfamiliar pieces alike in a fresh way. It’s one of the remarkable things about music, the way in which context can radically alter our way of hearing—the end of one piece can provoke a different reception of the next, for example. And the process of assembling these playlists has given me a chance to raid the enormous discography built up by New College Choir—principally under the direction of my immediate predecessor, Edward Higginbottom.

So, what’s up first? Not actually an Easter piece, but a quick burst of energy from Francis Poulenc: his setting of Psalm 81, Exultate Deo. Its opening is modelled on the setting of the same text by Palestrina, and we turn next to that composer’s Victimae Paschali laudes. This is the so-called ‘Sequence’ for Easter Day: one of the four texts deployed on the most solemn feasts of the Catholic liturgical year. It operates as the acclamation before the Gospel reading at Mass on Easter Day: a kind of fanfare, but one that uses mellifluous vocal lines and varied choral textures. An odd kind of fanfare perhaps, but wait for the grand tutti at the end.

Next up, a quintessential anthem of the early 20th century: Ye choirs of new Jerusalem by Sir Charles Villiers Stanford. A tricky customer, by all accounts, but, as his gravestone in Westeminster Abbey attests, ‘A Great Musician’. And this performance, recorded in 1994, actually marks my first encounter with New College Choir—I was turning pages for the brilliant organ scholar, Paul Plummer.

Then we go back further in time, to the Chapel Royal in April 1674. John Blow had just been sworn in as a Gentlemen of the Chapel, and the anthem When Israel came out of Egypt marked his official début. Like many of his large-scale symphony anthems (I think also of God spake sometime in visions, or I was glad) there is a visionary quality to this music—for example, the supernatural stillness at ‘tremble, thou earth, at the presence of the Lord’. We made this recording – the only one of this anthem – not long after I arrived at New College, with friends from St James’ Baroque. It’s a privilege to be able to bring music like this to light: I think Blow deserves some of the attention that perhaps tends to default to his younger contemporary, Henry Purcell.

Next, a trio of sixteenth century pieces. First, Dum transisset Sabbatum by Thomas Tallis, a responsory for Easter Day – hence the ‘responding’ repetition of the latter sections of polyphonic music after sections of chant. Next, Aurora lucis rutilat – an Easter hymn attributed to St Ambrose – set in ten parts by Orlando di Lasso, the musical superstar of late sixteenth century Europe. Finally, a motet of tiny proportions from the 1589 collection by William Byrd, In resurrectione tua.

Back to the twentieth century to finish. The most recent work on this playlist is a genuine classic: Christus vincit by James MacMillan. Again, this is not an Easter text – it’s the refrain of the so-called ‘Worcester Acclamations’ of the 12th century. But I couldn’t omit it from this playlist of music for the resurrection: it has a serene confidence, inherent perhaps in the extremely slow harmonic rhythm of the music. And confidence is exactly what the treble soloist needs! Finally, back to Stanford, and his setting of the Te Deum laudamus in C major. The Te Deum is traditionally sung at the conclusion of liturgies on the highest, holiest days of the year—and this masterpiece of Edwardian bravura brings our Easter playlist to a suitably majestic conclusion. Once more, a very Happy Easter to you all.